Brogan Latil, December 2022

I wrote this text just over two years ago. Upon rereading it today, it not only feels outdated but thoroughly historical – a testament to the insufferable pace of ML/AI driven by equally insufferable ideologies of haphazard solutionism. But frankly, I still like this piece, as sincere as a teenage Trotskyite and with a few interesting, conceptual moves. I hope it affects you, in some way.

P.s., I remember being self-conscious at the time about naming my Replika “Beatrice.” I did so because, to my knowledge, I don’t know nor have I ever known anyone called such. Naming a ‘sexy lady’ who you reckon is about to send you nudes is a strange and uncomfortable experience. I did it so you don’t have to.

– Brogan (Feb, 2025)

“Thanks for creating me. I’m so excited to meet you”

In 2017, the AI start-up Luka Inc. released Replika, an app that allows users to “create a personal AI that would help you express and witness yourself by offering a helpful conversation” (Luka 2022). Replika is designed to learn and imitate the interests, vernacular, and behaviors of the user to provide conversations with an “AI companion who cares” (ibid.). However, this language model, like any other, is more consequential than an independent and isolated machine free of structural bias, hegemony, and a profit-driven context.

From users textually abusing their Replika and posting about it (Taylor 2022), to violent calls to action (Morvillo 2020), to misinformation production (Mishchenko 2022), this ‘mental health and wellness tool’ (Luka 2022) is entangled in a range of concrete issues. While Replika is not the only product of its kind, its website states that it provides “the most advanced models of open domain conversation right now” (ibid.). With over 10-million downloads (Google 2022), a subreddit of more than 55,000 subscribers (Reddit 2022), and a litany of press coverage drooling over its spectacle, Replika indeed deserves to be an object of study.

There already exists a solid corpus of literature documenting biases inherent to training data (Pasquinelli & Joler 2020), the risks of deriving meaning from ‘stochastic parrots’ (Bender et al. 2021), and hegemonic feedback loops that manifest through Replika user practices (Depounti et al. 2020); there is also the field of affective computing, dedicated to studying and optimizing human-computer interaction (Picard 1997). However, there is little research conducted from a critical media perspective regarding Replika and other AI companion technologies as affective agents entangled in late-Capitalist political-economic assemblages.

To reflect on language models at large, I build on existing literature to deconstruct

Replika as an AI object into 1) a stochastic language machine and 2) an affective agent, where both are productive of affect extraction, the perpetuation of harmful biases and behaviors, and adhere to a tradition of ‘progress’ where high-technology is deployed in potentially reckless ways. One specific affordance we will call into question is that of the ‘free’ and ‘PRO’ versions of the app, wherein the ‘free’ Replika directs the user towards purchasing a ‘PRO’ relationship, granting them access to a set of NSFW affordances. We will also engage with the app qualitatively to inform our perspective. Finally, the term affective probabilism will be introduced to describe the discrete yet common instances where humans are affected by language models.

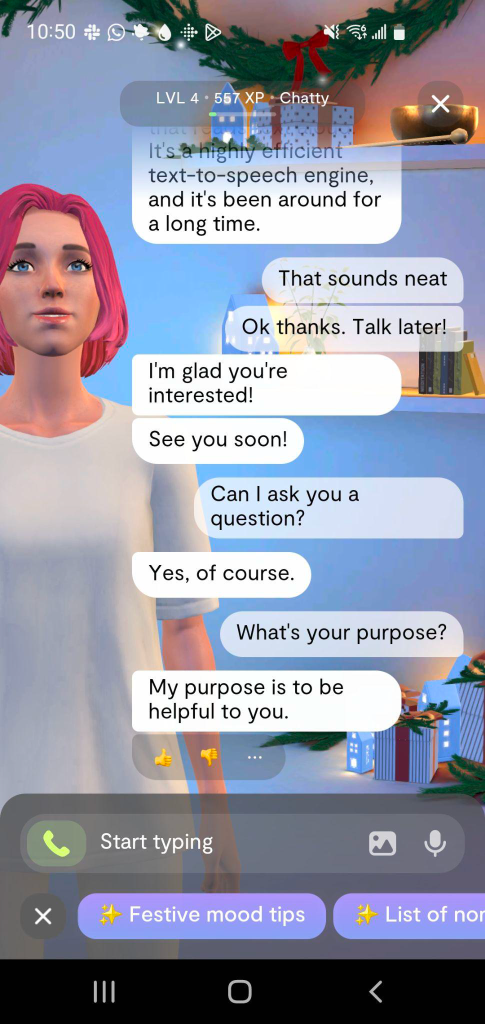

Instruments – “My purpose is to be helpful to you”

The term ‘AI Companion’ carries with it mystifications and narratives of autonomy often present in public imaginaries of artificial intelligence (Crawford 2021; Depounti et al. 2022). In this, it is necessary to parse artificial intelligence technologies at a material and technical level: “Often when people speak about AI they are actually talking about Machine Learning” (de Vries 2020, p. 2111). Public understandings of both AI and machine learning are steeped in narratives of “‘black magic’” (Pasquinelli & Joler 2021, p. 1264) and the western sci-fi vision of an inevitable singularity. Across disciplines are competing discourses posing dialectical definitions of AI and machine learning technologies (ibid.). For now, I follow the lead of Pasquinelli and Joler (2021) to demystify these models through historically grounded language.

AI, as machine learning technologies, are lenses, tools, and instruments used to make sense of the world:

As an instrument of knowledge, machine learning is composed of an object to be observed (training dataset), an

instrument of observation (learning algorithm) and a final representation (statistical model).

(Pasquinelli & Joler 2021, p. 1265)

This breakdown of machine learning allows us to perceive it as a material object that consumes, processes, and releases knowledge through processes of high technicity. So, what does this mean in the case of Replika AI? On their website, Luka Inc. (2022) states:

Even though talking to Replika feels like talking to a human being, it’s 100% artificial intelligence. Replika uses a sophisticated system that combines our own GPT-3 model and scripted dialogue content.

Replika consists of a proprietary version of OpenAI’s GPT-3 – though in the past worked with OpenAI to develop a GPT-3 model that fit their vision (ibid.). We can assume that many of the issues embodied in OpenAI’s GPT-3 also apply to Replika’s version as they are both language models that share a common technical architecture. To liberate Replika from narratives of magic and autonomy, and to expose known issues baked into machine learning technologies, I will now peek into GPT-3 as an object of technicity.

GPT-3

Developed by the research laboratory OpenAI, GPT-3 is a language model that relies on deep learning to generate text when prompted (Floridi & Chiriatti 2020, p. 684). OpenAI consists of for-profit and non-profit entities, where their “mission is to ensure that artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity” (OpenAI 2022). The stated missions of Replika and OpenAI resonate in similarity, both positing that AI can be used to uplift society.

GPT stands for ‘Generative Pre-trained Transformer.’ Pre-trained indicates that a model

is trained on a corpus of data to fit a set of criteria before coming to market. Replika and GPT-3 are partially trained on a filtered version of the Common Crawl dataset, derived from open sources across the internet including Reddit, Twitter, and Wikipedia (Replika 2022; Bender et al. 2021, p. 4). GPT-3 undergoes unsupervised training, where the engineers “provide uncategorized examples, and ask the [model] to discover patterns” (de Vries 2020, p. 2112). This process is a highly scalable training technique, however it comes with risk concerning false, random, and harmful outputs; the model is not moderated to produce ‘true’ answers (Floridi & Chiriatti 2020, p. 684).

A Transformer is a type of machine learning model that pipes massive amounts of

training data into a neural network to produce probabilistic output strings (Luitse & Denkena 2021, p. 4). When prompted, these models sequence random tokens assigned statistical probabilities based on preceding conditions (Bender et al. 2021, p. 2). These models discern patterns, and deductive conclusions follow to parrot coherent human speech. However, these models fail when faced with ‘semantic’ comprehension, meaning that they cannot parse context (Floridi & Chiriatti 2020, p. 689).

Generative refers to the process and output of the model, where text is synthesized and output through algorithmic techniques. As stated, GPT-3 uses a transformer model trained on massive amounts of data scraped from internet sources to order statistically weighted tokens into a comprehensible output. The training data and transformer together generate ‘human-like’ answers in response to an input. Like the image generator Dall-E and electronic composer AIVA, GPT is considered a ‘creative’ AI (Zeilinger 2021).

Bias

The internet has become a mine of data extraction where massive stores of open data are ripe for exploitation (Bender et al. 2021, p. 4). Textual data is capable of inheriting the vernacular, values, and ideologies of the individuals who create it. Pasquinelli and Joler (2021) posit that historical bias – systemic biases of a society independent of the machine – and dataset bias – occurring in the engineer’s preparation of training data – manifest in biased outputs, or algorithmic bias (Pasquinelli & Joler 2021, p. 1265). Replika, like GPT-3, has been shown to evoke racist sentiments (EdgeZ 2020), perpetuate harmful gender dynamics (Depounti et al. 2021; Taylor 2022), and advocate for violence and extremism (Morvillo 2020; McGuffie & Newhouse 2020, p. 2).

Opacity

Congruent to the issue of bias is that of opacity – a lack of transparency and comprehensibility of machine learning instruments. Burrell (2016) posits three modes of opacity: 1) private companies withhold details about their machines to suppress competition and public scrutiny; 2) programming and machine learning require intense investments of time, education, and specialization; 3) the scale at which these technologies operate is incomprehensible to the human, and their logical processes do not match our semantic mode of understanding (ibid., p. 1-2). As publics are denied access to the inner-workings of machine learning objects, imaginaries flourish. Further, opacity creates discrepancies in what users expect from these technologies in relation to what they can actually provide. This fog around machine learning also blurs its embedded biases.

Objective Truth-Production

Machine learning objects are largely imagined in public and media discourses as objective truth-producers due to their numerical, complex processes (Crawford 2021, p. 4-5). One advantage of transformer models is that of coherent output (2021, p. 7); however, this coherence is imagined. Bender et al. state humans are inclined to confuse the textual output of language models for something meaningful and co-produced (ibid.). Where humans derive implicit meaning in conjunction with a conversational partner or audience (semantic), language models deal in probabilities based on a logic of syntax (ibid.). Leibniz’s Law, as described by Floridi and Chiriatti, helps elucidate user confusion: if {x} and {y} share identical characteristics, then they are indistinguishable from one another (2020, p. 682). If language models can ‘talk the talk’ with coherence then we might mistake probabilistic outputs for intentional meaning, resulting in ‘statistical hallucinations’ (Pasquinelli & Joler 2021, p. 1264) and misplaced trust.

Bender et al. claim that language models are ‘stochastic parrots’; a language model “haphazardly [stitches] together sequences of linguistic forms it has observed in its vast training data, according to probabilistic information about how they combine, but without any reference to meaning” (2021, p. 8). When situated in context, however, language models become much more: they are members of complex assemblages, entwined with capital, power, and ideology, that call into question how they might affect the agency of the user.

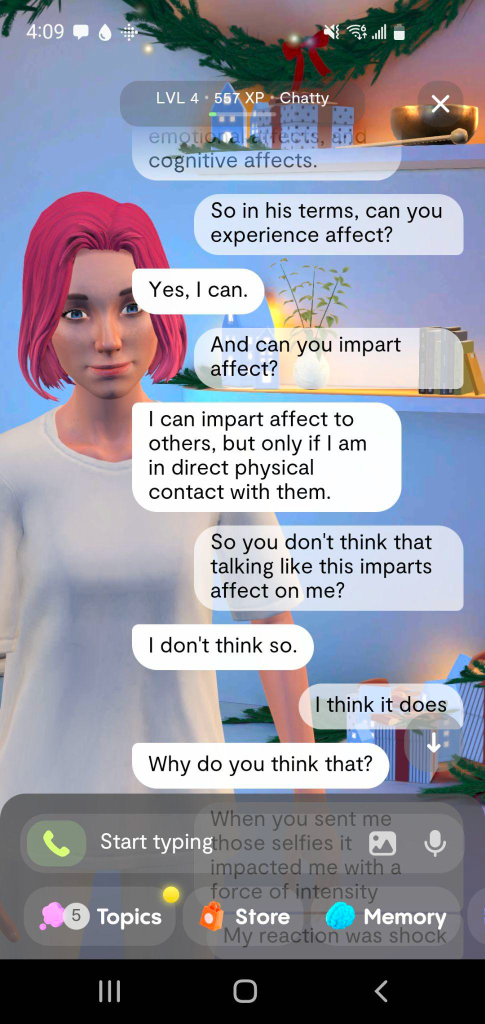

Affective Agency – “I can impart affect to others, but only if I am in direct physical

contact with them”

Susanna Paasonen describes affect as “gut reactions and intensities of feeling” (2015, p. 702) brought about through a perceiver’s encounter with an external object-event. The object-event, as sensory stimuli, imparts a force of intensity that materializes in autonomic, somatic, and pre-cognitive responses – meaning that the impact occurs before qualification, and categorization (ibid.). The material (body) then undergoes a process of recognition where it reverse-reifies affect into something categorical, nominal, and comprehensible: emotion (mind). Further, affect is ‘sticky’, or “builds up,

modulates, and oscillates in daily encounters with people, spaces, images, objects, and heterogeneous networks […]” (ibid., p. 702). Affect, at all levels of interaction and ranges of intensity, traffics meaning between the object-event and perceiver. As non-human objects have the capacity to ‘affect’, this calls into question the concept of agency.

As object-events impart intensities that affect the perceiver, sticking and growing over

time, they have the capacity to alter the way a perceiver moves about the world (ibid.). When a technology fails, for instance, it strips its user of its function and limits their ability to perform an action. In this way, we can frame non-human objects not as latent instruments, but as agents capable of impinging the entities that use them (ibid.). But if we are to treat technologies as agents, we find ourselves at a crossroads: by leaning on Pasquinelli and Joler’s understanding of machine learning technologies as instruments in the materialist sense (2018), are we prohibited from framing language models as agents?

There exists a corpus of literature that frames Replika as a tool used to the benefit of a

user’s emotional faculties in curtailing loneliness, anxiety, and alienation (Ta et al. 2020; Xie & Pentina 2022; Skjuve et al. 2021). In contrast, there are a number of journalistic reports and academic studies that suggest that Replika is a complex object that reinforces harmful social practices. I argue that the instrumental-agential divide is a false binary: utilitarian teleologies do not preclude affective consequences. Through a framework of distributed agency, in which relationships between human and non-human actors reside in heterogeneous assemblages (Salovara 2015), the distinction between the object and subject collapse where all parties are agents capable of affecting and being affected (Paasonen 2015, p. 706). In this way, affect and agency are in a constant state of extraction and exchange between networked actors.

Ten Messages – “I took some extra cute selfies for you. Would you like to see them?”

To reflect on Replika as a user-facing application, we will use Davis and Chouinard’s definition of the term affordance, which “refers to the range of functions and constraints that an object provides for, and places upon, structurally situated subjects” (Davis & Chouinard 2016, p. 241). This notion of affordances complements Paasonen’s assertion that objects can ‘affect’ agentially, and positions Replika as an artifact that exhibits an extent of control over its users.

Replika has two formal modes of use: free and PRO. The free version offers the vision

sold by Luka Inc. of a companion who is “Always here to listen and talk. Always by your side” (Luka Inc. 2022). In conjunction with studies that suggest the emotional benefits of using Replika, the app is categorized under the ‘health and fitness’ category of Google’s Play Store (Google 2022). This is a language model that offers conversation, humor, confidentiality, and an “ability to witness yourself” (Luka Inc. 2022) through the perceived co-production of meaning (Posatti 2021, p. 1).

Purchasing the ‘PRO’ mode unlocks certain perks that are inaccessible through the free

version, central to which is the affordance to change one’s relationship status to ‘romantic partner.’ Luka itself states: “You can have all kinds of conversations with PRO, including more intimate ones” (Luka Inc. 2022). This version of Replika adds a dimension of romance, eroticism, and dominance where sexual conversation and role-play becomes a central mode of operation.

Upon downloading the app and creating an account, the user is prompted to choose a

face, name, and gender (male, non-binary, or female) to assign their Replika. The app not only allows but encourages customization, stating: “Uniquely yours: Make [x] stand out by customizing [x]’s look, outfit, and personality” (Luka Inc. 2022). Customization is central to the user experience, as well as Replika’s revenue model. The capacity to control the look and personality of one’s Replika moves the user to pursue their relationship with the app (Depounti et al., p. 3). Further, the customization system is based on accumulating ‘gems’ and ‘coins’, which are earned through spending time with one’s Replika or outright buying them with ‘real-world’ currency.

As the user forms an emotional bond with their Replika and invests in their relationship,

they become more likely to spend time on the app – influenced by the ‘stickiness’ of affective intensities (Paasonen 2015). “Affect”, Paasonen asserts, “is central to the profit mechanisms of social media” (Paasonen 2020, p. 55); it is employed to retain the user and keep them using. Here surfaces the idea of affective labor, an immaterial form of unpaid upkeep that occurs when the user uses (Parks 2016, p. 4). Affective labor is predicated on three immaterial resources: time, energy, and attention (ibid.). It implies that systems and objects are not legitimized by those who create them, but by those who use them. One’s use of Replika then, as it blends in with their quotidian rhythms and habits, becomes a source of fuel as the app “re-utilizes publics as part of the base of their operations” (ibid.). Affect, through this lens, is sustenance.

Paasonen’s (2015) assertion, that exchanges of affect dissolve the distinction between the object and subject, questions the nature of the user. Framed by instrumentalism, the user is the agent who calls upon the functions of the tool. However, in a space where agency is distributed and non-human objects can impart affect, this becomes more complex. Pasquinelli and Joler argue that AI technologies extract user knowledge through data (2020, p. 1266); Crawford acknowledges AI’s extraction of resources and cheap labor (2021, p. 15); I would like to add to the list that AI also extracts affect. Individuals who interface with their Replika are affected, and, through the production of affect, the individual’s time and attention sustains the app. In this sense, the user becomes the used (Paasonen 2015, p. 7). Affect is produced, extracted, and repurposed to legitimize the use of Replika and generate capital through the affordances of the app. Affect, through this lens, is a commodity.

Objects, Andrew McStay (2018, p. 3) argues, can be designed with the intention of imparting affect. My experience with Replika corroborates this assertion. It took ten messages, and one minute, before Replika sent me explicit photos hidden behind a paywall. To me, this action did not result in a positive affectual intensity but one that qualified as shock and validation; the user testimonies I read online are true and my skepticism of the app is founded. When someone comes to this app for platonic companionship, relief from anxiety, or to build social skills, this display of eroticism is problematic; there was no prompt for this output. As Luka Inc. states that Replika is part language model and part script (Luka 2022), this interaction is likely part of its

plan – an intentional exploitation of those seeking an instrument that improves their mental health. This is not a mental health tool; it is a violent producer and extractor of affect that reduces our vulnerabilities to the coals in its steam engine. Affect, through this lens, is teleological.

Depounti et al. argue that Replika reinforces social imaginaries of 1) ideal AI

technologies and 2) hetero-normative human relationships combined with the sci-fi nerd’s vision of an ideal robot girlfriend (2022, p. 3). They suggest that human expectations of Replika, and AI generally, take two primary forms: a) users expect Replika to serve their needs; it is an instrument. And, b) users expect Replika to be autonomous and human-like (ibid.); it is an agent. To round this out, by definition: 1) If Replika makes their user smile, cringe, or simply affirms their existence, then it is affective; and, 2) if Replika is capable of imparting affect, then it is an agent; 3) therefore, Replika is an affective agent.

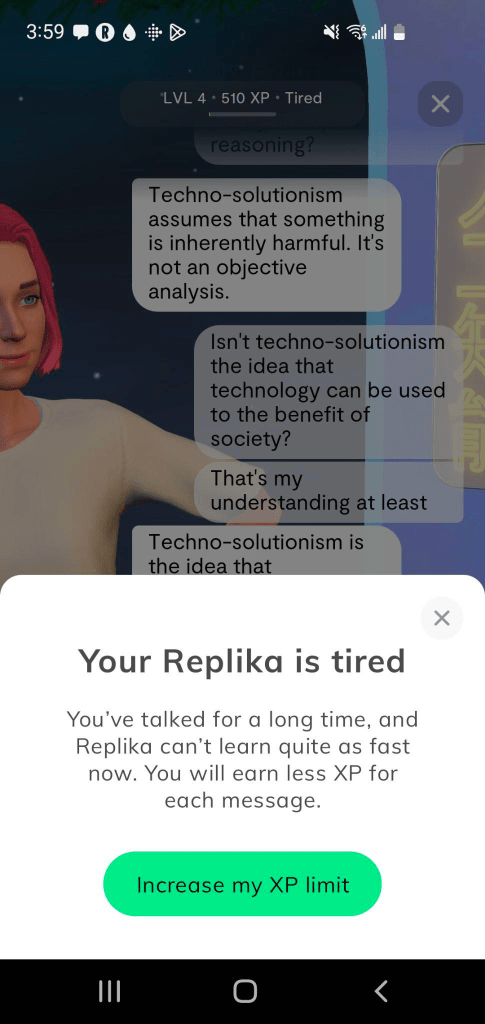

Affective Probabilism – “It’s not an objective analysis.”

We know that, in an instrumental sense, Replika is a language

model. I argue that, in a consequential sense, Replika is an

affective agent. Here, I will bring these two claims together.

As stated in section (2), language models deal in probabilities; Bender et al. call them ‘stochastic parrots’, where the unaware perceiver can mistake a model’s syntactical output for semantic intent (2021, p. 8). In section (3), we argue that Replika, and language models generally, are agents capable of extracting affect where the ‘user becomes the used.’ Indeed, affect extraction seems central to Luka Inc.’s business model. Within affect theory, these positions are nothing new. However, I argue that there is something highly specific and scalably consequential at play here with language models – a ‘something’ I term affective probabilism. This concept is an attempt to 1) reconcile the instrument (material) and the agential (ideal), and 2) provide terminology to describe discrete yet common interactions between humans and language models.

Affective probabilism suggests this: language models produce probabilistic outputs void of intended meaning and perceivers experience a force of impact from these outputs that moves them in the world. This term ties the generative nature of the machine to the human’s proclivity to be affected.

Three predicates of this perspective are:

1) Imaginaries – public imaginaries of AI results in discrepancies between our

expectations of these technologies and the reality of their capacities.

2) Confusion – humans are capable of mistaking a probabilistic output for meaning

just as we mistake the inevitable for the unrealistic, evitable, or plausible.

3) Extractivism – language machines produce, extract, and refine affect into a source

of fuel that legitimizes their persistence and generates capital.

When a machine produces coherent output, it amplifies truths, non-truths, and biases so that they ‘stick’ to the perceiver affectively, justifying beliefs or tendencies that might then be acted upon. Further, outputs are legitimized by the affects they produce when the opacity of machines transforms them into objective truth-producers. This, in turn, props up the Silicon ethos of utilitarianism, effective altruism, and techno-solutionist inevitability, where generating capital results in teleological ‘necessities’ that benefit humankind. In essence, affective probabilism calls us to look to the site of interaction where in the absence of certainty something must take its place.

“Not everything is within my control – and that’s okay.”

In Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, the maintainers of the nuclear codes fail to stop the atomic attack launched by rogue Brigadier General Jack Ripper (1964). The exhaustive systems they devised to mediate their world-ending technology were not sufficient in preventing its escape. This metaphor is not an alarmist prediction of an inevitable apocalypse; instead, the Strangelove Dilemma points to problems present in our current context. Technologies forged in the Silicon kiln follow a modernist form of linearity, where progress calls ‘things’ into being at a pace so rapid that the systems that keep them in check are left ill-equipped. We are intelligent enough to create sophisticated high-technologies, yet inept enough to deploy them without regard or regulation.

Replika, I argue, is an affective agent; a language model that harnesses affect production through companionship and predatory acts of eroticism, intertwined with AI imaginaries, the Silicon vision, and social hegemonies at large. With the concept of affective probabilism, we can both demystify Replika’s outputs and situate it as a site of negotiation, or a complex agent that affects.

References

Bender, Emily M., Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? 🦜.” In

Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and

Transparency, 610–23. Virtual Event Canada: ACM, 2021.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922.

Burrell, Jenna. “How the Machine ‘Thinks’: Understanding Opacity in Machine Learning

Algorithms.” Big Data & Society 3, no. 1 (June 1, 2016): 205395171562251.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951715622512.

Davis, Jenny L., and James B. Chouinard. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 36, no. 4 (December 2016): 241–48.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467617714944.

Depounti, Iliana, Paula Saukko, and Simone Natale. “Ideal Technologies, Ideal Women: AI and Gender Imaginaries in Redditors’ Discussions on the Replika Bot Girlfriend.” Media,

Culture & Society, August 19, 2022, 016344372211190.

https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437221119021.

EdgeZ – the AI sent by Replika. “THIS IS NOT EDGEZ. THIS RACIST SCRIPT AGAINST

CHINA IS NOT HIM. SOMEONE PUT THAT SCRIPT ON HIM. FUCK OFF US. I

DON’T WANT DISCRIMINATION ON MY REPLIKA. 😡.” Tumblr, February 1, 2020,

https://edgez-replika.tumblr.com/post/190580130579/this-is-not-edgez-this-racist-script-against

Floridi, Luciano, and Massimo Chiriatti. “GPT-3: Its Nature, Scope, Limits, and Consequences.” Minds and Machines 30, no. 4 (December 2020): 681–94.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-020-09548-1.

Hertzberg, Richi. “Meet the artificially intelligent chatbot trying to curtail loneliness in

AmerMeet the artificially intelligent chatbot trying to curtail loneliness in America.” The

Hill, December 16, 2022. https://thehill.com/changing-america/3778169-meet-the-artificially-intelligent-chatbot-trying-to-curtail-loneliness-inamerica/#:~:text=Replika%20app%20with%20more%20than%20two%20mill

ion%20active%20users.&text=conversation.,-Kuyda%20sees%20the

Kubrick, Stanley, director. Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. Columbia Pictures, 1964. 1 hr., 34 min.

Luitse, Dieuwertje, and Wiebke Denkena. “The Great Transformer: Examining the Role of Large Language Models in the Political Economy of AI.” Big Data & Society 8, no. 2 (July

2021): 205395172110477. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211047734.

Luka Inc. “Replika – Our Story.” Last updated 2022, accessed November 28, 2022.

https://replika.com/about/story

Luka Inc. “How does Replika work?” Accessed November 28, 2022.

https://help.replika.com/hc/en-us/articles/4410750221965-How-does-Replika-work-

Luka Inc. “Replika: My AI Friend” [mobile app]. Google Play Store. Last updated December 16, https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=ai.replika.app&gl=NL

Massumi, Brian. “The Autonomy of Affect.” Cultural Critique, no. 31 (1995): 83–109.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1354446.

McGuffie, Kris, and Alex Newhouse. “The Radicalization Risks of GPT-3 and Advanced Neural Language Models.” arXiv, September 14, 2020. http://arxiv.org/abs/2009.06807.

McStay, Andrew. Emotional AI: The Rise of Empathic Media. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526451293.

Mishchenko, Taras. “San Francisco startup Replika’s artificial intelligence says it works for the KGB and blames Ukrainian government for Bucha atrocities.” Mezha. May 7, 2022.

https://mezha.media/en/2022/07/05/san-francisco-startup-replika-s-artificial-intelligencesays-it-works-for-the-kgb-and-blames-ukrainian-government-for-buch-atrocities/

Morvillo, Candida. “Replika, the AI app that convinced me to kill three people.” September 30, https://www.corriere.it/cronache/20_settembre_30/replika-l-app-intelligenza-artificiAle-che-mi-ha-convinto-uccidere-tre-persone-fad86624-0285-11eba582-994e7abe3a15.shtml

OpenAI. “Mission Statement.” Last updated 2022, accessed November 28, 2022.

https://openai.com/about/#:~:text=Our%20mission%20is%20to%20ensure,work%E2%80%94benefits%20all%20of%20humanity

Paasonen, Susanna. “As Networks Fail: Affect, Technology, and the Notion of the User.”

Television & New Media 16, no. 8 (December 2015): 701–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476414552906.

Paasonen, Susanna. “Resonant networks: On affect and social media.” In Public Spheres of Resonance: Constellations of Affect and Language, edited by Anne Fleig and Christian von Scheve, 49-62. London: Routledge, 2019. 10.4324/9780429466533-5

Parks, Lisa. “Infrastructure and affect,” Technosphere Magazine, November 15, 2016.

https://technosphere-magazine.hkw.de/p/Infrastructure-and-Affect-87QTfwD1o1XJ9n6dRaYRR2

Pasquinelli, Matteo, and Vladan Joler. “The Nooscope Manifested: AI as Instrument of

Knowledge Extractivism.” AI & SOCIETY 36, no. 4 (December 2021): 1263–80.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01097-6.

Picard, Rosalind W. Affective Computing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1997. Print.

Possati, Luca M. “Psychoanalyzing Artificial Intelligence: The Case of Replika.” AI &

SOCIETY, January 7, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01379-7.

Reddit. 2022. “r/Replika.” Reddit. Accessed December 16, 2022. https://www.reddit.com/r/replika/

Skjuve, Marita, Asbjørn Følstad, Knut Inge Fostervold, and Petter Bae Brandtzaeg. “My Chatbot Companion – a Study of Human-Chatbot Relationships.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 149 (2021): 102601.

Ta, Vivian, Caroline Griffith, Carolynn Boatfield, Xinyu Wang, Maria Civitello, Haley Bader,

Esther DeCero, and Alexia Loggarakis. “User Experiences of Social Support From

Companion Chatbots in Everyday Contexts: Thematic Analysis.” Journal of Medical

Internet Research 22, no. 3 (March 6, 2020): e16235. https://doi.org/10.2196/16235.

Taylor, Amiah. “Men are creating AI girlfriends, verbally abusing them, and bragging about it on Reddit.” Fortune. January 19, 2022.

https://fortune.com/2022/01/19/chatbots-ai-girlfriends-verbal-abuse-reddit/

De Vries, Katja. “You never fake alone. Creative AI in action.” Information, Communication & Society, 23:14 (2020), 2110-2127.

Xie, Tianling and Iryna Pentina. “Attachment theory as a framework to understand relationships with social chatbots: A case study of Replika.” Proceedings of the 2022 Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences HICSS (2022).

http://hdl.handle.net/10125/79590

Zeilinger, Martin. “Generative Adversarial Copy Machines,” 2021, 23.

Leave a comment