March, 2023

Introduction

In November 2016, Richard Spencer raised his microphone under the banner of the alt-right and pledged loyalty to Donald Trump in the language of the Third Reich: “Hail Trump, hail our people, hail victory!” (Lombroso and Appelbaum 2016). Spencer’s critical gesture exposed a core distinction between the disunited belief systems of self-proclaimed members of the alt-right at this point in time; that of white supremacy vs. western chauvinism. Political scientist George Hawley (2017) asserts that “[a]ny political movement, if it grows large enough, will experience splits that lead to new debates about taxonomies” (p. 157). Indeed, certain far-right protagonists, namely Gavin McInnes and Mike Cernovich, deplored Spencer’s salute to the Third Reich and announced their departure from the group, cementing a rift between the white and civic nationalist.

According to Hawley (2017), ‘alt-lite’ is not used as a self descriptor, but is “used as a derogatory term by the Alt-Right” (p. 143) to signify those who left the movement due to its foundations in white supremacy. It is a label given to individuals who share beliefs with a range of more solidified online subcultures such as the ‘manosphere’ (Andrew Tate), neo-reactionaries (Curtis Yarvin), Libertarians (Lauren Southern), Trumpers (Ann Coulter), the Intellectual Dark Web (Jordan Peterson), radical conspiracy publics (Paul Joseph Watson), and, of course, the alt-right (Richard Spencer) (Hawley 2017; ADL 2022). The alt-lite, as a given name, appears synthetically and linguistically, but less so authentically and materially. Here emerge elements of complexity: who can we safely classify as alt-lite if no one will own up to it?

This study lies at the intersection of new media studies and subcultural studies. The goal of this work manifests in three entangled research questions, each at a different level of inquiry (macro, meso, and micro) and supported by complementary methodologies (mapping, delineation, and ethnography). Together, these questions aim to answer a meta question that is, what are we actually talking about when we talk about the alt-lite?

Macro – RQ1: What is the networked position and proximity of the alt-lite in relation to other subcultures, political ideologies, and content spheres on TikTok?

Meso – RQ2: Can we locate the boundaries of the alt-lite on TikTok, and if so what are their qualities?

Micro – RQ3: How can the hashtag, as a networked affordance, guide us in better understanding and defining the alt-lite?

The ultimate goal of this study is to problematize the taxonomy of the alt-lite through cartographic (macro), archeological (meso), and ethnographic (micro) approaches. The alt-lite, on an ideological level, appears as a confluence of proximate yet distinct belief systems and subcultures. As Ma (2021) rightly notes, existing academic and journalistic research has attempted to construct stable profiles of the alt-lite (Hawley 2017; Mudde 2019; Munger and Phillips 2022; Ribiero et al. 2020; Moyer and Stein 2017), but in doing so has in some cases produced disparate characterizations and definitions. The nature of the alt-lite is still an open question – one that might not be thoroughly answered through stable epistemologies (assumptions) but rather by exploiting the instability, precariousness, and ephemerality (questions) that comes with a group that does not name itself.

As the alt-lite was incubated in online spaces (Hawley 2017; Nagle 2017), this approach necessitates a digital site for observation. Maddox and Creech (2020) assert that platforms are spaces “where expressions of identity are commodified, quantified, and reinforced…” (pp. 610-611). TikTok was chosen due to its reputation as a political radicalizer as well as its robust visual and networked affordances that enable collective identity formation. As a site that functions on the logic of memetic visual and aural vernaculars (Zulli & Zulli 2022), this platform provides a space for digital subcultures to manifest materially. The affordances of TikTok give life to cultures of play, networked resistance movements, and disinformation flows often attributed to the far-right and conspiracy publics (Grandinetti & Bruinsma 2022). TikTok indeed has been referred to as a platform that traffics in ‘filter bubbles’ (Rogers 2019), recommending unknowing individuals harmful content via its personalization algorithms (Keith 2021; Binder 2021; O’Connor 2021).

To locate explicitly alt-lite content on TikTok is a challenge based on an assumption of an externally differentiated class of identity; if Gavin McInnes, a far-right provocateur, is collectively labeled alt-lite (ADL 2022), should we take that as the grounds of determination that anyone who mimics his beliefs, sentiments, and practices is as well? To make sense of the alt-lite on TikTok, I argue that we are better suited to delineate the platform mediated beliefs and practices assigned to it than the users who supposedly embody it. This framing is in line with the findings of Ma’s (2021) study on alt-lite creators on YouTube:

“I find that ‘alt-lite’ does not represent a coherent worldview but rather a collection of practices that help right-wing and far right personalities reconcile their stated color-blind worldview with their highly popular and profitable brand of reactionary politics” (Ma 2021, p. 12).

While this study does not concern influencer practices nor one’s position in the attention economy, Ma’s findings point one to isolate the incoherent characteristics ascribed to the alt-lite independent of the complexity of differentiation that comes with identity. As such, the subject-object of study cannot be the user as agent but instead subcultural belief and practice – generated by, but independent of, the individual. To frame the alt-lite as a set of qualities rather than a group of bodies, I will treat the ‘hashtag’ as a proxy for belief and praxis (Lewis 2018). As an affective affordance complicit in the shape and texture of socio-technical networks, the ‘hashtag’ can be seen as an actant in the Latourian sense (1987).

To treat the hashtag as a proxy results in a series of loci that one can safely say contains traces of the alt-lite; however, one hashtag can be used across cultural domains in synonymous, disparate, or incoherent ways. As a networked actant able to affect and be affected, meaning and utility can be thrust upon the hashtag by its connected actors. By reading hashtags as signifiers (Clarke et al. 1975), one may be able to draw out the ideological proximity and overlap of different subcultures and provide a material position to the imagined alt-lite. Essentially, the logic of this study is to ‘put the platform to work’ to map the contents it traffics and problematize our common ways of classifying these contents towards spatially characterizing the alt-lite as a subculture.

Making sense of the alt-lite, online

The imagined alt-lite is inextricably tied to the social reality and dominant culture of the United States in the 21st century. Indeed, subcultures do not exist in a vacuum but are products of and reactions to social forces at large (Young 1971). Encyclopedia Dramatica (2022), a “troll archive”, qualifies the alt-lite as “Civic Nationalist, Zionist, and Culturally Libertarian”. In other words, the alt-lite perceives western values of liberalism as superior to their alternatives, especially concerning individualism and unconstrained freedom of choice, resulting in a non-racial nationalism. According to Hawley (2017), the way these values manifest discursively is what sets the alt-lite apart from the alt-right. He argues that the alt-lite congregates around cultural and economic issues instead of racial ones, opposes Islam in its perceived anti-semitism and homophobia (rather than existential incompatibility), has a preference for Donald Trump, and generally supports Israel (Hawley 2017). In his definitions, Hawley (2017) leaves out a key component to characterizing the alt-lite, being online spaces.

According to Nagle (2017), the alt-lite quietly emerged in both popular and subterranean form prior to the 2016 US election. On YouTube and Twitter, idealogues built their platform and gathered an audience through “SJW cringe compilations” and ‘debunking’ the irrationality of the progressive left, while “ironic mememaking adolescent shitposters formed a reserve army of often darkly funny chan-style image-based content producers” on forums and message boards (Nagle 2017, p. 41). Here it seems that the alt-lite is defined less by a uniting belief system but by a common enemy, or ‘Other’ (Hebdige 1979). Digitally, the alt-lite appears as ‘youthful’, reactionary, and subversive, weaponizing digital formats and practices (memes, compilations, trolling, shitposting) to fight a culture-war through offensive and serrated humor. TikTok might not be the original breeding grounds for far-right discourses, but the effects of radicalization are felt in their ecosystems (Grandinetti & Bruinsma 2022).

Digital researchers, Ribeiro et al. (2020), share with Hawley the observation that the alt-lite disavows the alt-right’s banner of white supremacy, but “frequently flirt with concepts associated with it” through conspiracies like ‘The Great Replacement’ (p. 131). Munger and Phillips (2020) further contest Hawley’s claim that race is non-central to the alt-lite by analyzing user practices on YouTube. They state that the alt-lite emerges through “racist and otherwise offensive humor as a means to antagonize and upset… liberals and leftists” (p. 200). What the mentioned studies do agree on is who the alt-lite formulates as its enemies, namely “politically correct”, leftist progressives (e.g. Black Lives Matter, Social Justice Warriors, and Antifa). Ma (2021) problematizes the taxonomy of the alt-lite on the grounds of exposing a common ideology, stating: “Having spent many months immersed in the world of reactionary YouTube channels, however, it is not immediately clear to me that Mike Cernovich espouses a more extreme ideology than Steven Crowder” (Ma 2021, p.4). According to Ma (2021), the alt-lite emerges in online spaces as a set of reactionary practices that tie common uses of platform affordances to common issues, or ‘matters of concern’ (Latour 2004). When considered together, these studies evoke certain definitional commonalities with which to classify the alt-lite: the alt-lite 1) shares a common enemy, 2) embraces civic nationalism over overt racial nationalism, and 3) is highly fluent in their use of digital spaces.

As stated, the alt-lite is used as a generalization for the defectors of the alt-right (Hawley 2017); as a generalization, it does not embody identity on explicit and material traits but rather on the basis of a point of disagreement (white nationalism). As journalistic and academic researchers recirculated this term, it gained a power that was not necessarily earned. Cass Mudde (The Majority Report 2018) asserts that the main distinction between the alt-lite and alt-right is that the former believes in democratic forms of governance while the latter calls for an authoritarian mode of nationalism. Based on this distinction, Mudde says, the alt-lite falls under the ideological category of a “Radical Right” and should be called as such.

Methodology

Aligned with the tradition of Digital Methods (Rogers 2019), the operationalization of the research questions involves repurposing the affordances of TikTok to expose, identify, and scrutinize content spheres that function as subcultural publics. Specifically, the ‘hashtag’ functions as both the subject (actor) and object (cultural signifier) of inquiry. As a subject, the hashtag is treated as a unit of subcultural information due to its potential to signify and be signified, both shaping and shaped by the user practices that accompany it (Abidin 2021). As an object, the hashtag-as-signifier is the primary collection method due to its searchability as well as epistemological ordering, linking, and archiving capacities (siloing videos into ‘hashtag page’; transforming unlinked users into networked users) (Zappavigna 2015). This approach is ultimately grounded in a Latourian (1987; 2004) perspective where ‘meaning’ should not be thrust upon a set of actors at the onset of investigation but should iterate out of the descriptions issued by human and non-human actors themselves. Repurposing the hashtag towards data collection allows the researcher to use TikTok’s search function to query for a keyword resulting in a page of videos semantically associated with said query.

In a preliminary version of this study, I employed a research persona approach (Bounegru et al. 2022) by engaging with far-right content to condition TikTok’s recommendation system, resulting in a ‘radicalized’ account. Attempts to use the FYP to collect political content were unsuccessful, likely due to TikTok’s improved moderation system. This necessitated a systematic approach. Keywords derived from existing literature (Hawley 2017; Mudde 2019; Ma 2021) and primary sources (videos of Gavin McInnes, Milo Yiannopoulos, and Mike Cernovich) viewed on YouTube were collected and queried via the search bar. If these queries resulted in pages containing ideological content congruent with the alt-lite, the hashtags connected to political videos were collected and added to the query list. To justify collection, 10% of each hashtag page was viewed to confirm the presence of values and practices assigned to the alt-lite. These pages were analyzed manually to determine their level of ‘alt-lite-ness’. This snowball sampling technique resulted in a corpus of 16 hashtag pages and 9,535 videos (Figure 1).

The collected hashtag pages were captured from TikTok using the scraping tool Zeeschuimer and were then uploaded to 4CAT (Peeters 2022) to transform them into network files. These files were imported into Gephi to create co-hashtag networks. This ‘mapping’ approach (Rogers 2019) is used to expose thematic clusters of hashtags that could be attributed to a range of subcultures, ideologies, and content spheres present on TikTok.

To answer RQ3 necessitated an ethnographic approach. During the hashtag collection and manual analysis process, I took field notes based on the following questions:

- What does this hashtag signify in relation to the alt-lite and how does this signification relate to other uses of this hashtag?

- What kind of visual and aural content/practice accompanies this hashtag on the basis of format, theme(s), position(s), and audience engagement (comments)?

These field notes resulted in a collection of observations concerning the subcultural codes, signifiers, and practices embedded in hashtags associated with alt-lite beliefs. Coupled with the ‘mapped’ findings, these data are used to inform RQ2 by identifying the boundaries of alt-lite as a cultural site and qualifying these boundaries as stable, porous, non-existent, or otherwise. The collected data results in a temporal snapshot of the current iteration of the alt-lite, as issues central to a movement, ideology, or political subculture might shift over time.

Findings

Co-hashtag networks

When searching for figures central to the alt-lite, as determined by a range of sources (ADL 2022; Hawley 2017; Ma 2021), few were explicitly present on TikTok in the form of hashtags or captions. It seems that TikTok has increased their moderation of far-right personalities, as evidenced by a search for Richard Spencer (Figure 3). Similarly, Gavin McInnes, a far-right provocateur and founder of the Proud Boys, only appears in misspellings of his name, indicating that TikTok has attempted to scrub the platform of his presence. These misspellings of Gavin McInnes can be read as a strategic user practice to circumvent the moderation algorithms employed by TikTok and provide us with a way into this ideological space (Gerrard 2018). Surprisingly, Milo Yiannopoulos appears both in captions and as a hashtag.

With these limitations in mind, I scraped the videos from hashtag pages associated with Gavin McInnes (#gavinmcginnes, #gavinmcinnis, and #gavinmccines) and Milo Yiannopoulos (#miloyiannopoulos) and constructed a co-hashtag network from these data (Figure 3). This network is made up of eight thematic clusters which include traditional conservative, far-right, and leftist groups. The majority of the hashtags and associated videos are in line with the positions of McInnes and Yiannopoulos, while the top-most cluster is made up of self-proclaimed leftists (leftist-anarchists, socialists, and communists). Yiannopoulos is central to the network, connected to every cluster present, indicating that users associate him with these ideological discourses. His hashtag is often used with clips taken from pre-existing, long-form interviews and speeches not present on TikTok, pointing to cross-platform reposting practices by right-wing users. In the context of other hashtags (#feminismiscancer vs. #fascist), his name takes on a range of signifying utilities from allegiance to contestation. Here, we can see the fluidity of hashtags as signifiers when disparate groups appropriate a common sign to express opposing positions.

Gavin McInnes manifests less centrally in this network (Figure 3), instead appearing in three distinct clusters. It comes as no surprise that his name is used in the context of ‘anti-left comedy/trolls’, as he is well known for his subversive comedy. As a self-proclaimed ‘anti-woke’ civic nationalist, he also appears in the ‘maga/conservative’ cluster. While McInnes avoids labels of traditional conservatism, many of his talking points (ex. cancel culture, common sense rationalism, and traditional gender roles) feed into the ideological ecosystem of the liberal right. Here the values of the alt-lite are embedded and shared with traditional conservatism. A third iteration of his name is present as a bridge between the leftist cluster and the rest of the network, co-occuring with hashtags that signify disavowal (ex. #racist, #fascist). What is peculiar about these three iterations of ‘Gavin McInnes’ is that each misspelling is isolated to a specific, participatory inner-circle. His name travels diagonally across political camps (Tuters & Willaert 2022), though in discrete ways. The trolls, conservatives, and leftists each communicate with a slightly altered sign representing a common referent. As an affordance, the hashtag here functions as a bespoke signifying and epistemic ordering practice.

As depicted in Figure 1, 14 hashtags were collected based on their centrality to the past and present belief systems of the alt-lite. Both #altlite and #sheeple were removed from this network due to their low co-occurence frequency. Interestingly, I could not find current primary sources to corroborate Hawley (2017) and others’ identification of the alt-lite’s discourse surrounding Islam on YouTube or TikTok, likely due to content moderation and the ephemerality of ‘newsy’ concerns. It seems that the proclaimed alt-lite icons, at least on YouTube, have shifted their focus to the transgender ‘agenda’ and gender ideology – talking points of both the traditional right and far-right at the time of this study. Figures like Gavin McInnes have picked up biological determinism – a theory, commonly associated with Richard Dawkins and Jordan Peterson, that one’s physiology determines one’s gender and identity – to affirm the gender binary and contest the idea that an individual can transition to a sex not assigned at birth. This is depicted in the hashtag network above (Figure 4).

Seven clusters emerge in the 12 hashtag network (Figure 4) covering a range of issues including the traditional right, far-right, manosphere, and several gender-related discursive spaces. Also present are ‘trad family’ and ‘momtok’, two seemingly benign content spaces that do not explicitly identify politically but contain ideological undertones when parsed. While the seed hashtags appear to cluster centrally, this is due to the inter-connectivity resulting from the snowball approach. Exemplified by their distribution across thematic clusters, these hashtags indicate a connectivity across ideologies and their issue spaces. For instance, #feminismiscancer (a famous Milo Yiannopoulos one-liner) connects ‘momtok’ to the ‘traditional right’ and ‘far-right’ even though it is classed in the ‘anti-feminism/pro-man’ cluster. Similarly, #woke fastens ‘trad family’ to the ‘trad right’, ‘far-right’, ‘biological determinists’, and ‘redpill’ clusters. Although the seed hashtags are not visually present in every ideological space, they are directly connected to these spaces by the hashtags they are used in tandem with. This distribution indicates a non-centrality of the hashtags that embody characteristics of the alt-lite.

Qualitative hashtag analysis

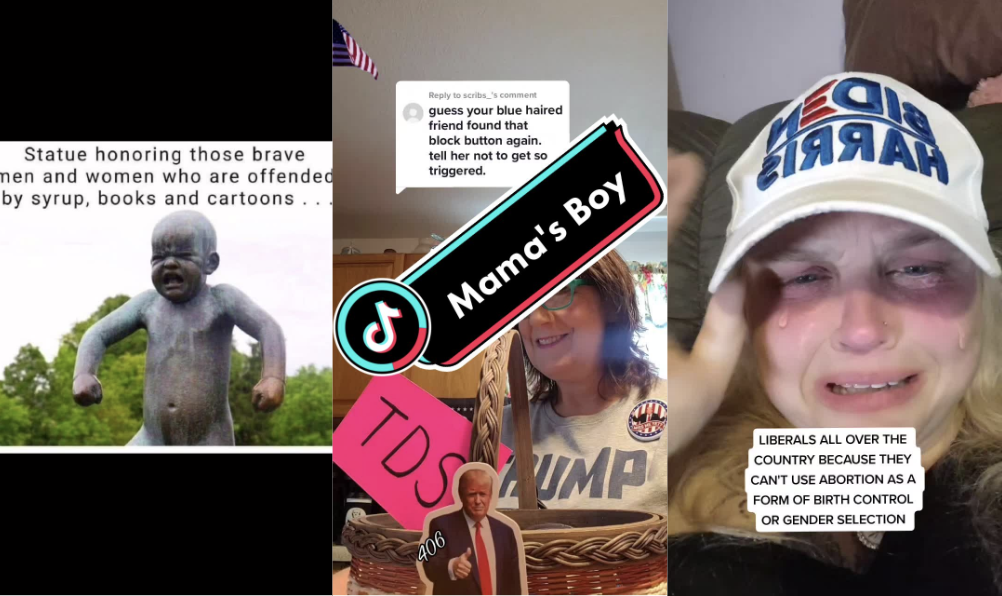

Through a qualitative analysis of the collected hashtag pages, I found that the majority of the associated content is not introspective but rather is pointed at the simultaneous construction and deconstruction of an imagined ‘Other’ (Hebdige 1979). The ‘liberal’, in our case, is used to signify the ‘Other’, an ideological differentiation that conflates hard-leftists, progressives, traditional liberals, and democrats. This taxonomy perpetuates and reifies an imagined enemy, whether it is Antifa, trans-rights activists, feminists, advocates for political correctness, or Joe Biden. Hashtags like #woke, #triggeredliberal, and #feminismiscancer define both the outsider and the self, affirming the defensible nest. The ‘liberal’, as an antagonist, coheres various right-wing movements around a common enemy, resulting in a loosely defined ‘in group’ and ‘out group’. The alt-lite’s allegiance to a common belief is not expressed in itself or by itself, but through an unspoken alliance of right-wing communities engaged in ‘semiotic guerrilla warfare’ (Hebdige 1979) via hashtags and their associated videos. This battle takes place through two main tactics: ‘subversive triggering’ and ‘common sense rationality’.

- Triggering the woke

Triggering (fig. 5) has become a discursive strategy commonly associated with internet trolls and shitposters that is meant to upset, disrupt, and offend individuals of a certain demographic or ideological stance (Bishop 2014). The goal of triggering, as described by a TikTok user, is not to win an argument but to “piss off liberals”. This practice is found on the majority of the collected hashtag pages, especially #maga, #freedomofspeech, #woke, #factsoverfeelings, and, of course, #triggeredliberal. This last hashtag is the epitome of this practice, and appears in both edgy ‘humor’ (attack-oriented sketches and one-liners) and ‘serious’ (defense-oriented monologues) content formats. Triggering also appears in the form of stylizing commodities (Hebdige 1979), where Trump apparel is foregrounded by the creator in an affective capacity to upset leftist viewers. Further, triggering as a practice is used by those across ideological spheres and subcultures whose common enemy is the ‘liberal snowflake’, including the traditional right, far-right, manosphere, red pill-ers, and biological determinists. As such, it is not a practice unique to the alt-lite.

2. Objectivity and common sense

The second tactic concerns using ‘facts’ derived through ‘common sense’ as ideological ammunition. This approach, like triggering, is found in traditional right, far-right, manosphere, red pill, and biological determinist spaces. Here, the right uses objective truths to discredit the ‘gender ideology’, feminism, systemic racism, and Covid-19 and vaccination discourses. Through a confusing mixture of rationalism and empiricism, users often reduce complex social issues to statistics (e.g. black on black crime) coupled with a priori forms of logic (e.g. men can’t be women because penis = man). In this mode of knowledge production, to embrace the ‘gender ideology’ is to be “anti-science”, a retooling of a common trope pointed at conservatives who undermine environmentalism and climate change narratives. Objective statements, as with ‘triggering’, are employed to counter the perceived absurdity and anti-logic of ‘wokeness’, and often appear with a nostalgia for “the way things used to be”. Users imply an ideal, sublime truth hidden behind the insidious guise laid by the liberal elite (e.g. Disney is grooming kids to submit to pedophilia) while simultaneously promoting an objective truth found in material superficialities (e.g. chromosomes determine gender). Again, this epistemological mode is shared across right-wing domains and, while used in the context of alt-lite values, is not unique to the alt-lite.

Discussion

To locate and study the alt-lite, I followed discrete characteristics of its proclaimed tenets. However, these tenets are often shared by other subcultures, blurring the boundaries between the alt-lite and other ideologies. When mapping these spaces, the alt-lite appears not as a distinct camp but as a number of qualities pre-present in traditional and far-right systems. These qualities, as hashtags, are distributed across subcultures and content spheres, revealing two main characteristics of the imagined alt-lite; it appears to be 1) rhizomatic – meaning the values of the alt-lite are not its own, but scattered amongst other belief systems with many points of entry, and 2) marked by ‘in-betweeness’ – an amorphous, non-committal, and fragmentary shape and proximity to surrounding belief systems and subcultures. As an imagined subculture, the alt-lite is in-between political camps (traditional and far-right), reactionary practices (trolling and austere discourse), and collective identities (MAGA and red pill). On TikTok, the alt-lite manifests not as a material group of human users (bodies) but as an imagined buffet of ‘practices as belief’ distributed across more distinct subcultural networks.

While Hebdige (1988) asserts that subcultures ‘hide in the light’, our light shines on an array of cultural artifacts (signifiers) that cannot be classified as unique to the alt-lite. In the findings of this study, traces of the alt-lite appear embedded in the cultural material of other reactionary publics. Archaeologically, this results in a ‘mixed-context’ where it becomes difficult, often impossible, to periodize and differentiate between like-materials of disparate cultures. The artifacts recovered are largely evidence of an alliance of right-wing communities engaged in semiotic warfare waged against a common ‘Other’ (Hebdige 1979). While we can more materially define the boundaries of the right on TikTok, delineating the alt-lite becomes moot without unique artifacts to stake as loci. What we think of as the alt-lite resides amongst the signifiers of more centralized right-wing spaces where subcultural identities blur together in an assemblage of media systems, signifiers, and practices. The boundaries of the alt-lite, then, are not its own but belong to the many cultural spaces it inhabits.

It is clear that hashtags, when contextualized in video content, can act as signifiers in the subcultural sense (Clarke et al. 1975); an object (the hashtag) is attributed meaning (political charge), and thus transforms into a signification of ideological allegiance, opposition, and identity. The hashtags then function as a form of both resistance and identification – a resistance to the imagined ‘Other’ as well as the perceived hegemonic forces at large (Hebdige 1979). The ‘woke lib’, as ‘Other’, becomes a pervasive, culturally specific spectacle, in the Debordian (1967) sense, as images of blue-haired SJWs and ‘Joe Brandon’ mediate the relations between distinct yet entangled ideological spaces. Ultimately, on TikTok I found no evidence with which to demarcate the alt-lite as a distinct subculture, but as a collection of characteristics endemic to others.

Because ‘alt-lite’ is not a self-identifier, it is difficult to say with certainty that I have looked in the right places and studied the right crowds. On the subcultural level, I found no signifiers, codes, or practices unique to the alt-lite with which to differentiate them from other, more centralized cultural sites. In this way, I agree with Mudde’s (Majority Report 2018) assertion that the alt-lite is a misnomer for beliefs and practices better situated in the ‘Radical Right’. Two personalities adorned with the ‘alt-lite’ label, Paul Joseph Watson and Mike Cernovich, espouse a congruent argument that the ‘alt-lite’ is a misnomer for the ‘New Right’ and ‘neo-conservative’ (Hawley 2017, pp. 153-154); these three classes beg for further research. Ultimately, I argue that the alt-lite is not a subculture of bodies but an imagined assemblage of historical conditions, (digital) media systems, and our proclivity as humans to categorize complexity for the sake of simplicity. It is a fictive taxonomy, an empty-signifier, and the bodies we associate with the alt-lite answer to other names. What we now consider to be the alt-lite, at least on TikTok, is not more than a swarm of politics that manifest as beliefs and practices co-produced by a number of right-of-center ideological spheres and subcultures.

References

Abidin, Crystal. “From ‘Networked Publics’ to ‘Refracted Publics’: A Companion Framework for Researching ‘Below the Radar’ Studies.” Social Media + Society 7, no. 1 (January 2021): 205630512098445. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120984458.

Anti-Defamation League. “From Alt Right to Alt Lite: Naming the Hate.” ADL, 2022, accessed on February 25, 2023. https://www.adl.org/resources/backgrounder/alt-right-alt-lite-naming-hate

Binder, Matt. “TikTok’s algorithm is sending users down a far-right extremist rabbit hole.” Mashable. March 28, 2021. https://mashable.com/article/tiktok-recommendations-far-right-wing

Bounegru, Liliana, Melody Devries, and Esther Weltevrede. (2022). “The Research Persona Method: Figuring and Reconfiguring Personalised Information Flows.” In Figure, Figuring and Configuration, edited by Celia Lury, William Viney, and Scott Wark, 77-104. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2476-7_5

Clarke, John, Stuart Hall, Tony Jefferson, and Brian Roberts. “Subcultures, Culture and Class.” In The Subcultures Reader: Second Edition, edited by Ken Gelder and Sarah Thornton, 100-11. London: Routledge, 1997 [1975].

Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. New York: Zone Books, 1995 [1967].

Encyclopedia Dramatica. “Alt-Lite.” Last edited December 28, 2020, accessed on February 25, 2023. https://encyclopediadramatica.online/Alt-Lite

Gerrard, Ysabel. “Beyond the Hashtag: Circumventing Content Moderation on Social Media.” New Media & Society 20, no. 12 (2018): 4492–4511. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818776611.

Grandinetti, Justin, and Jeffrey Bruinsma. “The Affective Algorithms of Conspiracy TikTok.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media (2022): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2022.2140806.

Hawley, George. Making Sense of the Alt-Right. Columbia University Press, 2017. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/hawl18512.

Hebdige, Dick. “Subculture: The Meaning of Style.” In The Subcultures Reader: Second Edition, edited by Ken Gelder & Sarah Thornton, 130-144. London: Routledge, 1997 [1979].

Iqbal, Mansoor. “TikTok Revenue and Usage Statistics.” Business of Apps. January 9, 2023.

Keith, Morgan. “From transphobia to Ted Kaczynski: How TikTok’s algorithm enables far-right self-radicalization.” Business Insider. December 12, 2021. https://www.businessinsider.com/transphobia-ted-kaczynski-tiktok-algorithm-right-wing-self-radicalization-2021-11?international=true&r=US&IR=T

Lewis, Rebecca. “Alternative Influence: Broadcasting the Reactionary Right on YouTube.” Data & Society (2018).

Latour, Bruno, “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam”. Critical Inquiry. Winter 2004.

Latour, Bruno. Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Lombroso, Daniel and Yoni Appelbaum. “ ‘Hail Trump!’: White Nationalists Salute the President-Elect.” The Atlantic. November 21, 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/11/richard-spencer-speech-npi/508379/

Ma, Cindy. “What Is the ‘Lite’ in ‘Alt-Lite?’ The Discourse of White Vulnerability and Dominance among YouTube’s Reactionaries.” Social Media + Society 7, no. 3 (2021): 20563051211036384. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211036385.

Maddox, Jessica, and Brian Creech. “Interrogating LeftTube: ContraPoints and the Possibilities of Critical Media Praxis on YouTube.” Television & New Media 22, no. 6 (September 2021): 595–615. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476420953549.

Moyer, Justin and Perry Stein. “‘Alt-right’ and ‘Alt-lite’? Dueling rallies planned for Sunday in D.C.” The Washington Post. June 23, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/alt-right-and-alt-lite-conservatives-plan-dueling-conservative-rallies-sunday-in-dc/2017/06/22/242d8de2-56bd-11e7-9fb4-fa6b3df7bb8a_story.html

Mudde, Cas. The Far Right Today. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019.

Munger, Kevin, and Joseph Phillips. “Right-Wing YouTube: A Supply and Demand Perspective.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 27, no. 1 (January 2022): 186–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220964767.

Nagle, Angela. Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right. London: Zero Books, 2017.

O’Connor, Ciarán. “Hatescape: An In-Depth Analysis of Extremism and Hate Speech on TikTok.” Institute for Strategic Dialogue (2021). https://www.politico.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/24/ISD-TikTok-Hatescape-Report-August-2021.pdf

Peeters, Stijn. “Capturing TikTok data with Zeeschuimer and 4CAT.” 2022.

Ribeiro, Manoel Horta, Raphael Ottoni, Robert West, Virgílio A. F. Almeida, and Wagner Meira. “Auditing Radicalization Pathways on YouTube.” In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 131–41. Barcelona Spain: ACM, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1145/3351095.3372879.

Rogers, R. Doing Digital Methods. London: SAGE, 2019.

The Majority Report W/ Sam Seder. “Why Alt-Right And Alt-Light Are Misleading Terms.” YouTube video, 7:50. January 22, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tROyePYFOCY&ab_channel=TheMajorityReportw%2FSamSeder.

Tuters, Marc, and Tom Willaert. “Deep State Phobia: Narrative Convergence in Coronavirus Conspiracism on Instagram.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 28, no. 4 (August 2022): 1214–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565221118751.

Young, Jock. “The Subterranean World of Play.” In The Subcultures Reader: Second Edition, edited by Ken Gelder and Sarah Thornton, 71 -77. London: Routledge, 1997 [1970].

Zappavigna, Michele. “Searchable Talk: The Linguistic Functions of Hashtags.” Social Semiotics 25, no. 3 (May 27, 2015): 274–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2014.996948.

Leave a comment