June 2023

Introduction

Over the better part of the past decade, governments, private institutions, journalists, and academics have attempted to provide definitions of disinformation, as well as offer optimal frameworks and methodologies of its study. It is a term that still resists a comprehensive and mutually agreed upon set of criteria. Bennett and Livingston (2018, 124) offer a provisional definition with which to begin: “intentional falsehoods spread as news stories or simulated documentary formats to advance political goals.” They conceptualize disinformation as rupture, manipulation, and redirection of information at a systematic level towards undermining or enhancing a political agenda. Similarly, the European Commission (2018, 3) and Freelon and Wells (2020, 145) position disinformation as a type of problematic information: “Disinformation… includes all forms of false, inaccurate, or misleading information designed, presented and promoted to intentionally cause public harm or for profit.” Both definitions consider an implied perpetrator, a truth-value, and a tactical intentionality to disinformation. What these definitions do not consider, however, are the subjects of disinformation.

One goal of this study is to further the project of fusing disinformation studies with

critical theory to further complicate our assumptions about how disinformation should be conceptualized and remedied (Young 2021). Disinformation is traditionally framed as an issue of epistemological veracity, that is truth vs. non-truth. However, more recent studies have begun to consider disinformation not only as an epistemological problem but one with an affective logic (Young 2021; Johnson 2018; Boler & Davis 2018; Blackman 2022). Affect theory allows the researcher to treat disinformation not only as a weapon of perception management, but as an agent in itself that moves subjects and activates publics through feeling.

I argue that paranoia (Sedgwick 2002), as a theory of negative affect, offers the

researcher an alternative understanding of disinformation as a resonant, contingent, and specific experience that moves subjects to take defensive action in a world marked by perpetual “bad surprises” (130). The issue at hand moves from conceptualizing information as true or false to complicating the affective intensities experienced by networked individuals that move them to form bespoke attachments to truth, units of knowledge, and modes of knowledge-production. Paranoia, I will describe, is an epistemological practice “of seeking, finding, and organizing knowledge” (ibid. 130) that is complementary to the uncertainty and confusion produced by disinformation.

To conceptualize the platformed subject’s affective relationship with disinformation, I

employ a qualitative comment analysis in the digital methods tradition (Rogers 2019). I take a case study of Dr. John Campbell’s YouTube channel, a retired nurse who accumulated a massive following during the Covid-19 pandemic for his medical-turned-political analysis. In the comment sections of four of his videos, I focus on how commenters construct relationships with the concepts of truth and disinformation presented in said videos. As sites of participatory culture (Jenkins 2006), comment sections are ambient geographies that can give rise to affective publics through storytelling, sentiment expression, and emotive resonance (Papacharissi 2016). This

approach reveals the paranoid logic that emerges when networked subjects are moved affectively by discussions of epistemological validity, grand conspiracy, and disinformation.

Dr. John Campbell

Dr. John Campbell joined YouTube in 2007, initially posting instructional medical videos for nurses in training. At the time of this study, he has published over 2,300 videos and accrued 2.81 million subscribers.

Initially, Campbell’s Covid-19 videos covered emerging global news, practices for

self-protection, and an accessible medical analysis of the virus aimed to inform the layperson. Over time, Campbell took on a more conspiratorial tone; his medical analysis gradually transformed into political and ideological analysis, which he claims to approach “objectively” and “scientifically.” Displayed on a banner behind him, his motto touts, “follow the evidence… wherever it leads…” As Health Feedback (2023) notes, many of his claims are indeed misleading and interpretive.

Creators like Dr. John Campbell proffer affective and emotive narratives through skepticism and fear in their diagnoses of why something is such a way, as well as hope and resolution in their prescriptions of how to treat the issue at hand. Lewis (2018) notes the success of micro-celebrities with alternative politics who establish credibility through relatability, authenticity, and accountability. Campbell exceeds at all of these, forming strong social bonds with his audience through his agreeable demeanor, medical expertise, and respect for his viewers. By developing a parasocial rapport, or feelings of intimacy and trust (Marwick 2015, 345), community members become attached to the creator through intensities of positive affect. These positive affective bonds, however, can occur through shared negative intensities (e.g. discomfort, anxiety, and fear).

Affective Publics and Paranoid Knowing

This study imagines affect in simple terms: “As both a precognitive force and a contingent sense of connection and relation, affect translates as vibrancy that varies in intensity and register” (Paasonen 2015, 703). Affect is a force imparted on a subject, occurring when something perceived becomes something felt. “Gut reactions and intensities of feeling” (702) result in a subject’s experience of an intensity before its recognition, manifesting in the sensation that something is coming. These intensities move the subject to act in some way and form ‘sticky’ attachments to the sources of said experiences, driving the subject to return to an affective state or avoid it by any means necessary. By facilitating attachments and relations between subjects and objects, affect “makes things matter” (703).

While affect is experienced subjectively, Papacharissi (2016) notes its capacity to be

shared, or resonant, through affective publics: “networked publics that are mobilized and connected, identified, and potentially disconnected through expressions of sentiment” (5). Affective publics are bespoke and situational sites of bond-formation where users share “affective statements of opinion, fact, or a blend of both” (10), forming cohesive assemblages out of disparate and distant bodies. Through subjective commonalities, shared experiences, and emotional resonance, affect connects and amplifies the testimonies of networked users, driving them to move and attach to objects and information in highly specific ways. The comment sections analyzed in this study, I argue, are affective publics characterized by a shared mode of paranoid sense-making.

Sedgwick’s model of paranoia (2002) provides a fitting schema with which to interpret

the affective relation that commenters form with (dis)information. Sedgwick (2002) calls for the depathologizing of the paranoid person; paranoia should not be framed as a condition to diagnose, but rather an emergent position taken by an individual who is moved to defend. As a theory of negative affect, paranoia is a position towards knowing through feeling (136). It is not an affective state, but rather an epistemological orientation towards mitigating the experience of negative affects (e.g. discomfort, anxiety, shame) (130). Ultimately, paranoia seeks to sniff-out, expose, and organize true knowledge hidden behind uncertainty. Sedgwick theorizes five characteristics of paranoia:

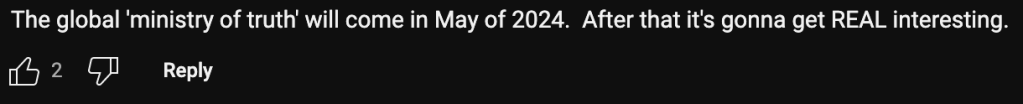

Anticipatory: “The first imperative of paranoia is There must be no bad surprises” (130). The paranoid position is an epistemological relation between the subject and

information that seeks to uncover knowledge before it is realized, so that the “bad

surprise” is always already known. The temporal reach of paranoia, as a theory of the

future embodied in the present, is infinite; there is no surprise too far in the future to be

speculated on and claimed as real. Resolution is not the telos of paranoia, as “it is more

dangerous for [the surprise] ever to be unanticipated than often to be unchallenged” (133). Instead, it is the pursuit of truth.

Reflexive and mimetic: “the way paranoia has of understanding anything is by imitating and embodying it”, so that “one understands paranoia only by oneself practicing paranoid knowing” (131). The paranoid knower is a loner, someone who ‘does their own research’ because no one can be trusted. This distrust is all encompassing; paranoia doubles itself into “a way of knowing” and “a thing known” (ibid.). To Sedgwick, the paranoid subject can only be truly understood by other paranoid subjects, and can only feel at home in a community of like knowers. The paranoid subject finds safety in paranoid relations, even if they cannot ensure resolution. Surely, “it takes one to know one” (ibid.).

Strong theory: a strong theory refers to “the size and topology of the domain that it

organizes” (134). Strong theories provide general ontologies and etiologies to

phenomena, or “an insistence that everything means one thing” (136). Paranoia, as a

theory of humiliation, reduces all uncertainties to imaginaries of potential shame, which enables a greater need to speculate on such scenarios before they occur. The drive to imagine and interpret information as truth, as well as construct “the Other” who is perpetrator, becomes even stronger as the paranoid position fails to stop the bad surprise. Upon their humiliation, the paranoid knower squints harder, at once narrowing their worldview and intensifying it.

Theory of negative affects: the paranoid position leverages the possibility of negative

affect, orienting the subject to anticipate them at all costs. Anticipation functions towards the “goal of seeking to minimize negative affect” (136), of mitigating the bad surprise. The paranoid position acts to “forestall pain” by exposing the unknowable – which is in itself pleasurable (137). The pleasure derived from paranoid knowing becomes cyclical as “one’s pleasure at knowing something could be taken as evidence of the truth of the knowledge” (138). In this, the threat of negative affect can transform under pressure into positive intensities – a sense of healing, belonging, satisfaction, thrill.

Exposure: the paranoid subject seeks exposure in two ways – to expose information so

that it becomes known, and to expose the ‘self’ so that they might be acknowledged (138). To the paranoid subject, to be known is the fantasy of resolution as they are

incapable of stopping the bad surprise – only anticipating its arrival. Exposure is deeply

narrative, expressed through sentiment and subjective experience. Paranoid suspicion

detracts from the energy of resolution (140); exposure is a movement towards

resolution, but is not in itself capable of resolution.

As a position, paranoia is a relation towards some perceived or imagined information,

executed through anticipation and exposure. The color of paranoia is something like deep skepticism, a suspicion that what is being depicted as true and real is a distraction from some hidden truth (133). Although paranoia is a position, it is still contagious (125); in affective publics (Papacharissi 2016), paranoia passes from body to body through resonant affective experiences, imitation and cultural production, and modes of meaning making. As these relations fail to properly anticipate and halt the bad surprise, it becomes true that “one can never be paranoid enough” (Sedgwick 2002, p. 142).

Methodology

This study is concerned with how platform users construct relations, negotiate with, and make sense of disinformation as both concept and event. To study the affective relations and epistemological positions of users, I take a digital methods approach to repurpose certain affordances of YouTube (Rogers 2019), the most prominent of which being the comment section.

Comment sections can operate as sites of participatory culture through the capacity of the audience to publicly and collectively engage with published content (Jenkins 2006). On YouTube, comment sections are sites of “intense collective sense-making and knowledge production” that can circulate information, opinion, and rhetoric that would likely be removed if posted in video-form (Ha et al. 2022, 2). Graham & Rodriguez (2021) note the importance of comment sections for users to collectively assess the validity and value of information, constructing relations with truth and knowledge. Comment sections can also sustain affective publics, or mediums which “activate and sustain latent ties that may be crucial to the mobilization of networked publics” (Papacharissi 2016, 310).

Using YouTube Data Tools (Reider 2015), a total of 16,281 comments were collected

from the comment sections of four videos published by Dr. John Campbell (Figure 3). The criteria for video selection included the centrality of “disinformation” and “truth” as primary themes, a substantial comment section (+2,500 comments), and an element of recency. Two of the videos issue suspicion towards the “Counter Disinformation Unit”, a cell of the UK government concerned with seeking out and mitigating the effects of online disinformation. The other two videos offer an interpretation of the political construction of “truth” by governmental and institutional authorities.

Before data was formally collected, I engaged in a preliminary ‘deep hanging out’ in the

comment sections to familiarize myself with the community and assess their heterogeneity, character, and discursive elements (Geertz 1998). After formal collection, the comment sections were combined into one master-set. While some might argue that this method dislocates the comment from its context, my aim is not to ignore context but to treat each comment as its own unit of data – as an affective locus and agent in itself.

Video title | Year published | View count | Likes | Comments |

Counter disinformation unit | 2023 | 246k | 23k | 4,757 |

Single source of truth | 2023 | 160k | 14k | 2,879 |

Government Counter Disinformation Unit | 2023 | 320k | 25k | 5,105 |

Post truth world | 2023 | 225k | 24k | 3,540 |

| Total | 16,281 |

With the field notes from the initial ‘deep hanging out’ in context combined with a

random sample of comments (n=1,000; 6.1%) derived from 4CAT (Peeters & Hagen 2022), I employed a multi-step, open-coding scheme (Strauss & Corbin 1990) to categorize comments based on the style of their relationship with disinformation discourses. The ideological positions of comments are not taken into account here, but rather the modes in which they articulate their positions – through critique, fantasy, sentiment, etc. This approach allows us to identify the affective practices that emerge when users communicate their relationship with disinformation. One comment might contain multiple styles of communication and intensity, and the derived categories are not mutually exclusive; I consider the coding scheme to indicate qualities of the observed comments rather than forming strict taxonomies. While this method leans towards empiricism, this study is self-admittedly ‘paranoid’ in its application of theory to the observed data.

Findings

A qualitative analysis of the comment corpus (n=16,281) resulted in informal, general reflections through field notes as well as a more structured coding scheme. The comment sections analyzed are characterized by a homogeneity in theme and heterogeneity in the mode of articulation. The comments overwhelmingly represent a distrust of institutional authorities. Further, the narrative style and intense sentimentality of the comments indicates high levels of affective resonance between commenters, Campbell, and the topics of discourse. To better grasp how relationships with disinformation are constructed and expressed affectively, I distilled the comments into three, non-exclusive practices of paranoid attachment consisting of exposure, anticipation, and reflexive and mimetic. Within these practices are six sub-categories, defined below.

Exposure

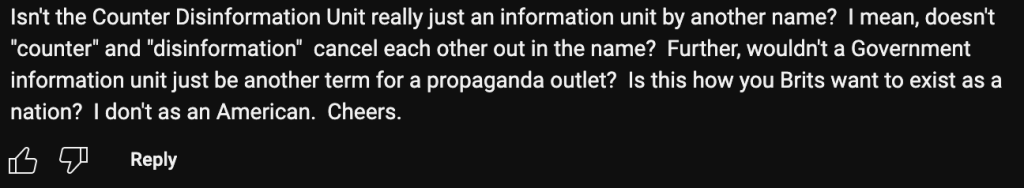

Critique of authority

Authority, especially governments and politicians, are a primary target of speculation and

suspicion in the comments collected. This critique is expressed when an imagined or known

authority, such as the UK government’s relationship with the BBC, is perceived to be the perpetrator of mass-control, manipulation, and violence at collective levels. Disinformation is framed as a weapon or tactic of knowledge-control by which authorities ensure their domination over the subject through perception management. Critical commenters attach a clean and accessible etiology of disinformation and truth to highly political narratives of authoritarianism, communism, and anti-democratic leftists. This form of critique renders authorities incapable of ever producing “truth” as they are always already the enemy of the individual.

Construction of “the Other”

Similar to critiques of authority, commenters assign perpetration to imagined or real parties and individuals in their attachment to disinformation. This manifests in the practice of attributing a perceived issue to a specific or ambiguous group of people, institution, or out-group. Perceived political opponents are called upon to signify the commenter’s membership to the in-group or attempt to justify the veracity of the commenter’s claims on the a priori basis that “the other” cannot be right. “The other” is framed as the source of disinformation or propagators thereof, which provides the commenter with a target of anticipation and speculation marked in time and space. In these comments, there is a presence of racial and ethnic ‘dog-whistles’.

Anticipation

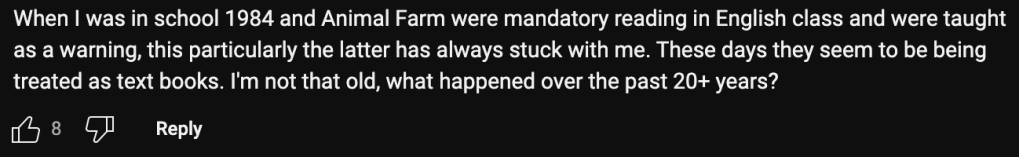

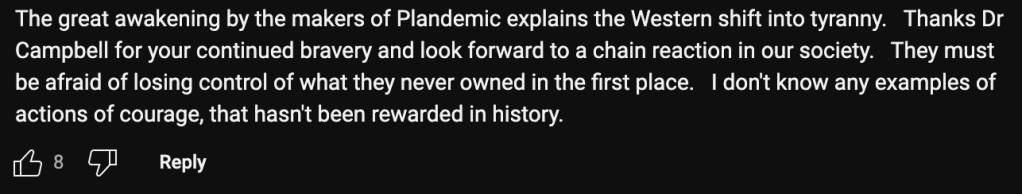

Extrapolate fantasy and existing conspiracy

Commenters often cite external media sources and grand-conspiracy narratives when making

sense of disinformation, embodying practices or positions where commenters attach information to fictional or imagined scenarios where sense can be accessed more easily. This includes dystopian media (e.g. 1984, Brave New World) or existing conspiracy theory narratives (e.g. The Great Reset, New World Order). Framing disinformation in this way both allows commenters to express their material concerns easily through a fantasy-proxy, amplifying anticipation and affective resonance, as well as draw fantasy into the material world to explain what cannot be known. This form of attachment is imaginative, speculative, and collectively produced, providing safety in fantasy.

Epistemological negotiations

Many comments reflect the users’ inclinations to “do the hard work” of epistemological

reasoning, exposing and delineating what is true and what is not. Here, disinformation is framed not only as a systemic issue but a moral and existential imperative inherently entangled with truth, reason, and science. This labor is represented in general practices of trying to make sense of something not known and who has ownership over knowledge. Often, the position taken by the commenter is that truth can be reached through “common-sense” schemas and positivist, evidence-based scientific processes. Here, we often see a contradiction emerge where “science” is framed as a fallible, disinformative institution, while the commenter proclaims their execution of science as true, valid, and infallible. This results in a tautological mode of knowledge-production where truth takes a concrete form through “empirical” judgment and a priori claims are confused with induction. As Campbell states, “follow the evidence… wherever it may lead…”.

Reflexive and mimetic

Deep resonance

Personal testimonies are central to the formation and maintenance of affective publics (Papacharissi 2016), where the commenter reflexively imagines the information at hand within their own context. Affective resonance appears in expressions of subjective experience and emotion, often communicated through narrative storytelling. These comments function both as declarations of emotion derived from the video, or topic thereof, and appeals to the emotion of the comment’s target. Sentiment expression and subjective narrative expose the commenter, allowing them to be acknowledged by someone else. Subjective negotiations with disinformation and “the other” are expressed through highly personal, contingent, and emotive experiences.

Affirmation and heroification

Critique takes many forms, including through positive, emotive attachments. Many comments praise the video creator, for “doing the hard work.” By framing him as an information-hero, comments indicate that the commenter not only identifies Campbell as a trustworthy source of knowledge, attaching to him on a personal level, but affirm his mode of sense-making as complementary to their own. Commenters express their position towards disinformation through declarations of positive affect, which signify in-group membership and an idolization of Campbell. These statements expose the commenter to the figure they put their faith in – the figure that might offer some form of resolution.

–

Through exposure, anticipation, and reflexive and mimetic practices, commenters perform their relationship with and imagination of disinformation in both statements of affect and affective statements. These data demonstrate the participatory nature of comment sections (Jenkins 2006), as knowledge is produced and sense is made in conversation between Campbell and commenters. The findings also give shape to an understanding of the affective public (Papacharissi 2016), where affect derived from experience and information becomes realized, circulated, and resonant in the comment section. Through attachments to an anticipatory and self-derived mode of knowing, a construction of “the Other”, and a collective telos towards exposing the perpetrator and the perpetrated, this affective public takes on a quality of suspicion. Consistent with Sedgwick’s model of paranoia (2002), I argue that these spaces can best be understood as paranoid publics.

Discussion

Paranoia emerges from experiences with or resonant narratives of negative affect (Sedgwick 2002). Those who take up the paranoid position may have experienced pain, discomfort, and rupture in the past that moves them towards a defensive, skeptical, and antagonistic stance in anticipation of an imagined future. A paranoid interpretation of users’ engagement with disinformation sheds light on how information can be deployed to leverage affect; indeed, affect “can inflame existing social and political conflicts. It can manifest through attacks on scientific evidence and by the seeding of mistrust in institutions” (Zelenkauskaite 2022, 4-5). Through affect, disinformation becomes ‘sticky’ (Paasonen 2015), deeply personal (Papacharissi 2016), and a moral imperative.

In the paranoid position, times of precarity (like the Covid-19 pandemic) drive individuals to search for meaning and assign value to phenomena to protect against the inevitable “bad surprise” (Sedgwick 2002, 130). The subject’s fear of humiliation shapes their mode of knowing, which preconditions an attachment to truth based in affect and emotion rather than informational veracity. This mode of knowing manifests in a defensive stance of absolute suspicion where subjects protect themselves against all parties that do not share their position. To paranoid subjects, only other subjects of paranoia can be trusted: “it takes one to know one” (131). Commenters attach to Campbell, as a stronghold of paranoia, in the promise of resolution. When traditional media circulate Covid-19 guidance measures, paranoid subjects cannot help but anticipate harm and suspect deception in their fear of humiliation; any information can become disinformation through the paranoid position of I know it when I see it. Paranoia analyzes specific and local events through sweeping generalities indicative of a strong theory (133), reducing uncertainty and complexity to clean, accessible explanations.

The collected comments reveal paranoia and disinformation’s double relationship: 1) disinformation is information perceived to obscure or work against truth, issued forth by some agent of perpetration, and 2) disinformation can be perceived as actual truth framed by said agent as a deceptive narrative. Through exposure, paranoia makes knowledge perceived as disinformation ‘real’ which further legitimizes paranoia, telling the subject that they can “never be paranoid enough” (142). This relation drives the subject to “put their faith in exposure” to make the truth, their truth, known to others as a step towards resolution (138); through critical, reflective, and narrative commenting practices, the subject does just this. Through speculation, they expose information as true or false to mitigate the negative affects of the bad surprise. Through fantasy, they expose the perpetrator to claim a source and etiology. Through sentiment, they expose themselves so that they might be helped. The pleasure derived from exposure, from revealing the ‘truth’, results in a doubling down on paranoid knowing, as feeling is confused with veracity; if it feels bad it must be real, and if it feels good it must be true. In this way, disinformation and paranoia are reciprocal, symbiotic, and mutually amplifying.

So then, what does Sedgwick’s model of paranoia (2002) offer to disinformation studies

in terms of resolution? For one, it acknowledges subjective experience, feeling, and perception to better understand how individuals construct relations with disinformation and truth. Second, disinformation agents can cultivate and leverage paranoia online to redirect uncertainty and confusion into frustration and suspicion, turning individuals against informational authorities and one another. Lastly, paranoia allows us to imagine affective remedies for affective issues; Sedgwick (2002) proposes that the opposite of paranoia is the depressive position, which seeks to maximize positive affect through reparative epistemologies (136). While a reparative reading of disinformation is outside the scope of this study, I believe it is beyond worthy of investigation towards devising strategies which may soften the conditions that drive individuals to become paranoid and smooth the turbulence that comes with networked disinformation.

References

Bennett, W Lance, and Steven Livingston. “The Disinformation Order: Disruptive Communication and the Decline of Democratic Institutions.” European Journal of Communication 33, no. 2 (April 1, 2018): 122–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317.

Blackman, Lisa. “Future-Faking, Post-Truth and Affective Media.” edited by Joanna Zylinkska, 59–78. London: Goldsmiths Press, 2022. https://www.gold.ac.uk/goldsmiths-press/publications/the-future-of-media/.

Boler, Megan, and Elizabeth Davis. “The Affective Politics of the ‘Post-Truth’ Era: Feeling Rules and Networked Subjectivity.” Emotion, Space and Society 27 (May 1, 2018): 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2018.03.002.

Campbell, John. “Counter Disinformation Unit.” YouTube video, 17:52 minutes. June 11, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yxKL_BPVl3E.

Campbell, John. “Government Counter Disinformation Unit.” YouTube video, 20:05 minutes. June 4, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yxKL_BPVl3E.

Campbell, John. “‘Single source of truth.’” YouTube video, 10:24 minutes. June 9, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AlSdCTx762M.

Campbell, John. “Post truth world.” YouTube video, 5:32 minutes. May 23, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tp8K3iW2QrU.

European, Commission. “Final Report of the High Level Expert Group on Fake News and Online Disinformation | Shaping Europe’s Digital Future,” March 12, 2018. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/final-report-high-level-expert-group-fake-news-and-online-disinformation.

Freelon, Deen, and Chris Wells. “Disinformation as Political Communication.” Political Communication 37, no. 2 (March 3, 2020): 145–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1723755.

Geertz, C., 1998. Deep hanging out. The New York review of books, 45 (16), 69.

Graham, Timothy, and Aleesha Rodriguez. “The Sociomateriality of Rating and Ranking Devices on Social Media: A Case Study of Reddit’s Voting Practices.” Social Media + Society 7, no. 3 (July 1, 2021): 20563051211047668. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211047667.

Ha, Lan, Timothy Graham, and Joanne Gray. “Where Conspiracy Theories Flourish: A Study of YouTube Comments and Bill Gates Conspiracy Theories.” Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, October 5, 2022. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-107.

Health Feedback. “Reviews of articles by: John Campbell.” Health Feedback. 2022-2023. https://healthfeedback.org/authors/john-campbell/.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

Johnson, Jessica. “The Self-Radicalization of White Men: ‘Fake News’ and the Affective Networking of Paranoia.” Communication, Culture and Critique 11, no. 1 (March 1, 2018): 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcx014.

Lewis, Rebecca. “Alternative Influence: Broadcasting the Reactionary Right on YouTube.” Data & Society, September 18, 2018.

Marwick, Alice E. “You May Know Me from YouTube: (Micro-)Celebrity in Social Media.” In A Companion to Celebrity, 333–50. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118475089.ch18.

Paasonen, Susanna. “As Networks Fail: Affect, Technology, and the Notion of the User.” Television & New Media 16, no. 8 (December 2015): 701–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476414552906.

Papacharissi, Zizi. “Affective Publics and Structures of Storytelling: Sentiment, Events and Mediality.” Information, Communication & Society 19, no. 3 (March 3, 2016): 307–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1109697.

Rieder, Bernhard. “YouTube data tools.” Computer software. Vers 1, no. 5 (2015).

Rogers, R. Doing digital Methods. London: SAGE, 2019.

Sedgwick, Eve. “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay Is About You.” In Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity. Duke University Press, 2002.

Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet M. Corbin. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc, 1990.

Young, Jason C. “Disinformation as the Weaponization of Cruel Optimism: A Critical Intervention in Misinformation Studies.” Emotion, Space and Society 38 (February 2021): 100757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2020.100757.

Zelenkauskaite, Asta. Creating Chaos Online: Disinformation and Subverted Post-Publics. University of Michigan Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.12237294.

Leave a comment